Warren Buffett’s Annual Letters – 2018

As part of our series on Warren Buffett’s Annual Letters, we look at the letter for 2018, which was released over the weekend.

Contents

Warren Buffett’s Annual Letters – 2018

We’ve previously looked at Warren Buffett’s letters that cover 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009 and 2008.

Today we’ll examine the 2018 letter, which was published over the weekend.

Performance

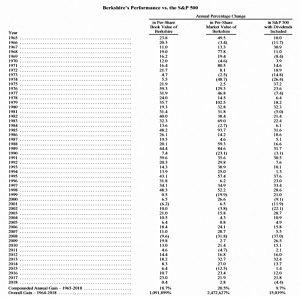

Over the 54 years to 2018, BRK has compounded its per share book value at 18.7% pa and its share price by 20.5% pa.

- This 1.8% difference has compounded to a 1.5 million percent difference over this time.

- During the same period, the S&P 500 has compounded at 9.7% pa (dividends included).

Under GAAP rules, BRK earned $4.0 bn in 2018:

- $24.8 bn in operating earnings

- $3 bn loss on intangible assets (through the Kraft Heinz deal)

- $2.8 bn capital gains on sales of investments,

- and $20.6 bn loss from unrealised capital gains on investments (“mark to market”).

Warren doesn’t believe the inclusion of the last line (new for 2018) to be sensible, since there will be large swings in profits from market movements.

Our advice? Focus on operating earnings, paying little attention to gains or losses of any variety.

I don’t have a problem with the change personally – BRK has investments, and they fluctuate in value.

- Updating the market price once a year seems fine, but the quarterly statements during a difficult year like 2018 will have been somewhat confusing.

Warren also announced that he is retiring book value as a metric, for three reasons:

- BRK now has its major value in operating business rather than in stocks.

- The operating companies have to be included at original book value, whereas the equity holdings are now marked to market.

- BRK will repurchase shares at more than book but less than intrinsic value, which makes per share intrinsic value go up, and per-share book value go down – this widens the gap between the book value and what Warren calls “economic reality”.

The business forest

Warren compares BRK’s “many and diverse businesses” to a forest, and tells investors to forget about the trees.

Let me remind you of our prime goal in the deployment of your capital: to buy ably managed businesses, in whole or part, that possess favorable and durable economic characteristics.

We also need to make these purchases at sensible prices.

Warren also stresses BRK’s two-pronged approach:

- Buy whole businesses (or at least 80% of the company)

- Buy 5% to 10% of a listed firm

This is an over-simplification: BRK has four large holdings of between 25% and 50% – Kraft Heinz being the best-known member of this group.

The minority ownership route has offered more value recently:

- In 2018, BRK bought $43 bn of “marketable equities” and sold just $19 bn.

EBITDA

It wouldn’t be an annual letter without an attack on EBITDA, and 2018 is no different:

Managements sometimes assert that their company’s stock-based compensation shouldn’t be counted as an expense. (What else could it be – a gift from shareholders?)

And restructuring expenses? Well, maybe last year’s exact rearrangement won’t recur. But restructurings of one sort or another are common in business.

Abraham Lincoln once posed the question: “If you call a dog’s tail a leg, how many legs does it have?” and then answered his own query: “Four, because calling a tail a leg doesn’t make it one.”

The only thing that BRK adds back to GAAP earnings is amortization costs from acquisitions ($1.4 bn in 2018).

- Warren also says that BRK’s depreciation charge of $8.4 bn understates what the firms needs to spend in order to stay competitive (the “maintenance capex”).

Investments

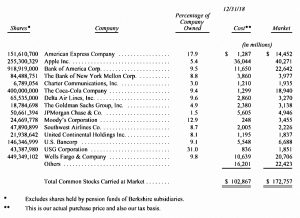

BRK’s investments are now worth £173 bn, though selling them would cost $14.7 bn in tax.

- Note that Kraft Heinz is excluded from this list because BRK is part of the control group, which means they need to account for the holding via the “equity method”.

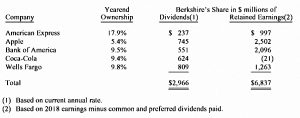

These investments paid BRK $3.8 bn in dividends in 2018, but just the five largest holdings also retained another $6.8 bn in earnings (BRK share).

- Depending on the likely future returns from these companies, retaining the cash could be the better option.

Buybacks

Share buybacks are in the news at the moment, with Democratic senators planning to outlaw them.

Warren clearly doesn’t agree:

All of our major holdings enjoy excellent economics, and most use a portion of their retained earnings to repurchase their shares.

We very much like that: If Charlie and I think an investee’s stock is underpriced, we rejoice when management employs some of its earnings to increase Berkshire’s ownership percentage.

Obviously, repurchases should be price-sensitive: Blindly buying an overpriced stock is value destructive, a fact lost on many promotional or ever-optimistic CEOs.

BRK itself bought back $928M of shares in 3Q18, at around 1.35 times book value.

- Before then, 1.2 times book had been the ceiling for purchases.

But as we saw earlier, Warren no longer sees book value as a good guide to the intrinsic value of the firm.

- It’s likely that BRK bought back more stock in 4Q18 – as the share price was lower – but I couldn’t find any reference to this in the annual letter.

Cash

Berkshire held $112 billion at year-end in U.S. Treasury bills and other cash equivalents, and another $20 billion in miscellaneous fixed-income instruments. We consider a portion of that stash to be untouchable, having pledged to always hold at least $20 billion in cash equivalents to guard against external calamities.

I will make expensive mistakes of commission and will also miss many opportunities, some of which should have been obvious to me. At times, our stock will tumble as investors flee from equities. But I will never risk getting caught short of cash.

Warren doesn’t expect to use that cash to buy more businesses – prices are “sky-high” at the moment.

Non-insurance businesses

Warren notes that although the pre-tax income from the non-insurance businesses rose by 24% to $20.8 bn, the post-tax return rose by 47%.

- That’s because Trump’s tax cuts reduced the main corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%.

This has resulted in a major increased in the intrinsic value of BRK and its constituent firms.

Float

Our property/casualty (“P/C”) insurance business has been the engine propelling Berkshire’s growth since 1967. P/C insurers receive premiums upfront and pay claims later.

This collect-now, pay-later model leaves P/C companies holding large sums – money we call “float” – that will eventually go to others. Meanwhile, insurers get to invest this float for their own benefit. As our business grows, so does our float.

We may in time experience a decline in float – at the outside no more than 3% in any year. The nature of our insurance contracts is such that we can never be subject to immediate demands for significant sums. That structure is by design and is a key component in the unequaled financial strength of our insurance companies.

Warren admits that competitive pressure means that insurance firms earn sub-normal returns on tangible net worth – but the use of the float more than compensates.

- As it happens, BRK’s insurance operation has been profitable for 15 of the last 16 years, earning $27 bn (pre-tax) in that period.

Debt

We use debt sparingly. Many managers will disagree with this policy, arguing that significant debt juices the returns for equity owners. And these more venturesome CEOs will be right most of the time.

At rare and unpredictable intervals, however, credit vanishes and debt becomes financially fatal. A Russian roulette equation – usually win, occasionally die – may make financial sense for someone who gets a piece of a company’s upside but does not share in its downside.

But rational people don’t risk what they have and need for what they don’t have and don’t need.

This is slightly misleading again.

- Because of the insurance float, some analysts have calculated that BRK has run a historic gearing of up to 1.6 times.

Fees

Warren began investing in 1942, some 77 years ago, with $114.75.

If my $114.75 had been invested in a no-fee S&P 500 index fund, and all dividends had been reinvested, my stake would have grown to be worth (pre-taxes) $606,811 on January 31, 2019. That is a gain of 5,288 for 1.

A $1 million investment by a tax-free institution – say, a pension fund or college endowment – would have grown to about $5.3 billion. If that hypothetical institution had paid only 1% of assets annually to various “helpers,” its gain would have been cut in half, to $2.65 billion.

That’s what happens over 77 years when the 11.8% annual return actually achieved by the S&P 500 is recalculated at a 10.8% rate.

The message is clear – keep your fees low.

- How many private investors are paying even more than 1% pa?

Warren also notes that if he had turned his $114 into gold, it would now be worth $4,200 – less than 1% of the same value invested in stocks.

Conclusions

It’s a fairly short and quiet letter this year, but with some good stuff as usual.

BRK came into this release on the back of a sharp fall in the Kraft Heinz share price, and Warren has all but admitted that he overpaid on that deal.

Analysts were also keen to hear:

- What happened with Oracle, bought in Q3 and dumped in Q4.

- What will happen to BRK’s growing cash pile.

- Whether there has been anymore work on succession planning.

- Why BRK has been such an enthusiastic buyer of banks (JPM and BoA) recently.

- More about the worker healthcare initiative (better outcomes, lower costs) with Amazon and JP Morgan.

They will have been disappointed on all fronts.

Warren did talk about the tax changes, share repurchases and the ability of the insurance division to weather the increased risk from natural disasters.

- Which is something.

Maybe we’ll hear more about the next big deal – and about succession planning – in the 2019 letter.

Until next time.