Weekly Roundup, 18th July 2022

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with inflation.

Inflation

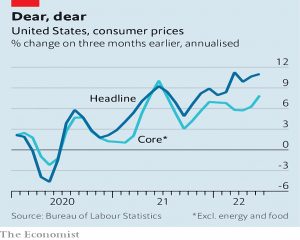

The Economist reported another upside surprise for US inflation and looked at the recession risks.

- CPI was up 9.1% year on year, against an 8.8% forecast – a four-decade high.

Stocks fell as markets digested more monetary tightening and the increasing risk of a recession.

The Economist was more concerned about the rise of core inflation (after the more volatile food and energy prices have been removed).

- Core inflation went up 0.7% in the month, the highest monthly increase for a year.

The annualised rate over the last three months is 8%.

Bond markets increased the likelihood of a full 1% interest rate rise at the Fed’s July meeting, but Fed officials have since signalled that they will stick with the planned 0.75% rise.

- Even this would lead to the steepest tightening since Volcker in 1981.

Falling energy costs might bring down the headline figure next month, but they might rise again as we approach winter.

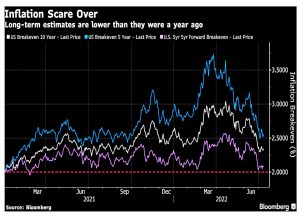

- But five-year breakevens and consumer expectation surveys are predicting lower rates as they expect the Fed to cut again if/when a recession materialises.

Authers

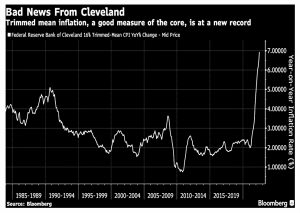

John Authers also looked at the inflation data in his Bloomberg newsletter.

The Cleveland trimmed mean hit its highest value ever (the series began in 1984).

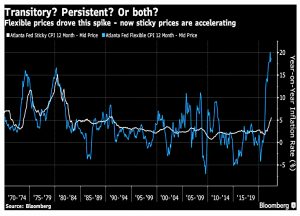

Inflation has been largely driven by “flexible” prices but worryingly, “sticky” prices are now also shooting up (this seems to be similar to the Economist’s “core” figure).

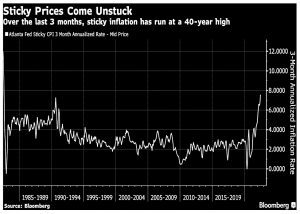

Over the last three months, sticky inflation is running at an annualised 8%, a 40-year high.

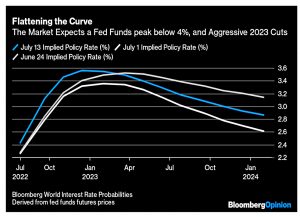

Bond market expectations are for a peak Fed rate of 3.6% in January 2023, after which there should be cuts.

The entire curve is higher than it was on July 1, when growth fears were stronger. But by comparison with June 24, it’s noticeable that the peak is barely any higher, and that the market at that point did not expect such a dramatic cutting campaign next year. The shift to a belief in a rapid exit from tight monetary policy is intact.

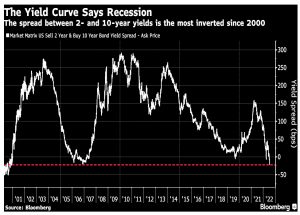

That’s because a recession is expected as the yield curve inversion shows.

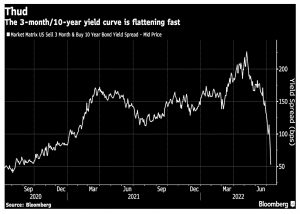

The three-month/10-year yield curve is less closely watched but tends to be an even better recession indicator, only inverting close to a recession. This measure had shown little recessionary anxiety for more of this cycle, and carried on widening into early May. That has now changed.

Breakevens are now lower than a year ago because markets expect the Fed to keep hiking until something breaks.

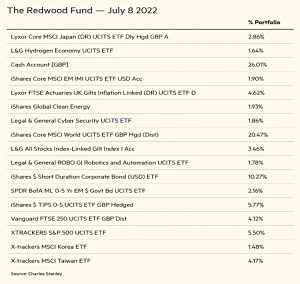

Redwood

In his regular FT column, John Redwood said that valuations are now becoming realistic but he remained worried about central banks overshooting and creating a recession.

When the leading central bankers met late last month at Sintra there were admissions that they had got inflation wrong last year. They greatly underestimated how high it would go and how long it would last. There was silence on whether expanding money and credit had anything to do with it.

Central bankers prefer to blame supply shocks (from Covid and the Ukraine war) exclusively, but they appear committed (particularly in the US) to slowing the economy through interest rate rises in order to reduce inflation.

John is optimistic about economic prospects in 2023:

Wage increases will fall short of peak levels of price rises, and that by next year inflation will be on the way down. This also means that output will slow and central banks will come to the view that they have done enough tightening. If and when this becomes clearer, bond and share markets can start to make some upwards progress.

But there will be earnings downgrades and profit warnings first, so he remains heavily in cash (26%).

Dividends

Also in the FT, Merryn Somerset Webb advised us to take cover and look for dividends.

- In general, I think this is poor advice (dividend stocks are nothing special), though there will always be those who need continuing income from their portfolio during a market downturn.

She notes the lack of visible stress amongst private investors:

Scottish Mortgage is still the most popular investment trust on buy lists (an odd thing given that it is at the epicentre of the market meltdown). However, [it] makes a certain kind of sense. After all, most of us have still made a little money in nominal terms over the past two years and quite a lot over five.

Interactive Investor clients are up 13.2% over two years and up 2.6% since just before the Covid crash.

- Of course, stock valuations remain higher than the long-term average and crashes usually overshoot rather than simply mean revert.

GMO’s “comfort model” suggests the US CAPE should be around 19, rather than its actual value of 28.

- That implies a further fall of 15%, and even more if earnings surprise to the downside.

Merryn suggests looking at investment trusts, where discounts to NAV have widened from 2.2% at the start of the year to an average of 9.5%.

- The average for the past decade is 4.7%.

Private equity has some of the largest discounts – 30% for Oakley Capital and 36% for NB private equity.

- But Merryn prefers dividends – the FTSE-100 should deliver more than 4% per year.

She recommends three trusts:

You can get 2 per cent off NAV at Murray International (yielding 4.5 per cent) and JPMorgan Claverhouse (4.7 per cent). And 10 per cent at the Lowland Investment Company (5.4 per cent).

Government borrowing

The Economist looked at the impact of higher interest rates on government budgets.

- Governments have borrowed a lot since the 2008 financial crisis, with low rates shielding them from the cost, and Covid made things worse.

The rich world borrowed 10.5% of its GDP in 2020 and another 7.3% in 2021, even as long-term bond yields plunged.

Official forecasts of interest bills now underestimate the likely peak in interest rates.

- The US forecast is for a 2.6% peak in 2024, but markets expect 3.6% in January 2023.

The UK’s interest bill should reach 3.3% of GDP in the current tax year, the most since 1989.

- The main problem here is that 25% of our debt is inflation-linked.

As well as the amount of debt and the proportion of floating rate and inflation-linked, the other factor is maturity.

- Longer-dated debt will not be refinanced for years, limiting the impact of current higher rates.

The normal measure is weighted average maturity (WAM).

- Britain’s WAM is a very healthy 15 years, but the average can be skewed by a small amount of very long-dated debt.

40-year bonds rather than 20-year bonds will improve a nation’s WAM but not affect the impact of rising rates over the next few years.

- The OBR has suggested we use median maturity instead, which The Economist terms the interest-rate half-life (IRHL).

Britain’s IRHL is around ten years.

There’s also the impact of QE to consider – the central-bank reserves used to buy bonds are floating rate.

- This has been profitable historically since markets have assumed interest rates would rise earlier than they have.

This helps risky countries like Italy the most, but the effect is now going into reverse.

We find that QE reduces Britain’s interest-rate half-life to just two years, meaning 50% of Britain’s government liabilities will roll on to new interest rates by late-2024.

Japan and Italy fare even worse by this measure, though interest rates will probably not rise in Japan, which has low inflation.

It seems tempting to unroll QE quickly, but this would lead to capital losses.

- Another option is to pass the costs to regular banks by paying interest on only a tranche of their reserves.

Japan and Europe already have a tiered system.

Whether it is banks, taxpayers or bondholders, somebody has to pay the bills that are now falling due. Soaring interest costs will further squeeze government budgets already under pressure from higher energy costs, rising defence spending, ageing populations, slowing growth and the need to decarbonise.

Monetary policy rules

The Economist also looks at the use of monetary policy rules to determine the appropriate interest rate.

- Back in February, the Fed dropped this section from its semi-annual report to Congress because it would have suggested rates of around 9% when they were actually close to zero.

The search for rules dates back to the 1930s when Henry Simons, an American economist, argued that authorities should aim to maintain “the constancy” of a predetermined price index.

There was also a monetarist version:

In the 1960s Milton Friedman called for central banks to increase the money supply by a set amount every year. That was influential until the 1980s, when the relationship between money supply and GDP broke down.

The popular choice today is the Taylor rule, invented by a Stanford economist in 1993.

The only variables were the pace of inflation and the deviation of GDP growth from its trend path. Plugging these in produced a recommended policy-rate path which, over the late 1980s and early 1990s, was almost identical to the actual federal-funds rate.

But in the late 1990s, the Taylor rate was systematically lower than the Fed rate.

- Variations with different weightings, an inertia term and the use of forecasts rather than current values were developed.

The Fed report now mentions five options, but they all would have suggested tightening before it happened.

- The Cleveland Fed uses seven rules and constructs a median value from them. (( I’m a fan of geometric means myself, but I don’t work for the Fed ))

Using this as a reference point, Mr Powell and his colleagues ought to have started raising rates gingerly in the first quarter of 2021 and should have brought them to roughly 4% today.

I like this rule – for me, interest rates should have gone up as soon as the Covid vaccine was discovered.

Quick Links

I have six for you today, the first two from The Economist:

- The Economist looked ahead to Europe’s winter of (energy) discontent

- And explained how the war in Ukraine could revive America’s uranium industry.

- Pragmatic Capitalism said that deflation is now a bigger risk than prolonged inflation

- UK Dividend Stocks said that a bear market would bring the FTSE-100’s CAPE to an attractive level

- Musings on Markets had a mid-2022 update on country risk

- And Alpha Architect found momentum everywhere, including in factors.

Until next time.