Weekly Roundup, 8th June 2020

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT with Merryn Somerset Webb, who was wondering whether value investing might make a comeback.

Value vs Growth

Merryn Somerset Webb began by admitting that her UK value tips from a post-Brexit referendum UK in 2017 hadn’t worked out.

- But at least she spotted that Woodford’s flagship fund was to be avoided (because of its unlisted stocks).

It’s a year since that fund was suspended, which is why she was thinking of it.

- She’s still of the opinion that given time, a lot of the funds’s holding might have come good.

Individual stocks don’t necessarily revert to the mean in any consistent way. But

markets do.

Which brings her to growth vs value.

At some point what you have to pay for a great and growing company matters more

than the greatness itself. Now we are at the very end of one of these cycles.

I can’t dispute that the gap between growth and value stocks is as large as its been since 1904.

- The Price-to-book gap (possibly a discredited measure, see below) is now at 12 times, compared to the long-term median of 5,4 times.

But without quoting Keynes, that doesn’t mean it’s about to change tomorrow.

- The bits of the post-Covid landscape that we can make out today seem to support the growth stocks.

And even Merryn points out:

The scarcer growth is, the more you are prepared to pay for it. The lower interest rates are, the less you are bothered about the lack of immediate cash return from that growth.

But she still likes cheap and is prepared to wait.

The growth vs. value debate has been a popular one in recent weeks.

- James Anderson from tech IT Scottish Mortgage put the cat amongst the pigeons by saying that the value style has been “an investment tragedy”.

He said that Warren Buffett’s “extraordinary grip” on the investment world had “sanctified a freezing of the investment narrative”. He called Buffett the face of an “outmoded doctrine” that had condemned savers to poorer returns.

I don’t entirely buy the idea of Buffett as a value investor, at least since the 1950s.

- He’s more of a QARP (quality at a reasonable price) guy for me, with a few sharp hedge fund-style moves around the edges.

But let’s run with it – Buffett is certainly not a fan of the expensive tech growth stocks – that he might or might not understand – favoured by Anderson.

In the Times, Ali Hussain asked whether this was the death of Buffett-style investing.

- Ali notes that along with Woodford, other famous value investors (some of which are strictly equity income investors) such as Mark Barnett, Alex Wright, Ben Whitmore and Tom Dobell has also underperformed.

This is not such a big deal for me – fund managers are supposed to do what it says on their tin, and investors should allocate assets between them according to the styles that they think will outperform (or alternatively, they can buy and hold index funds).

Perhaps a better question is any value has failed in recent years.

Book value is the foundation of value investing, and its relevance is arguably less in the internet age.

- Tangible book value (or net asset value, NAV) is the total of the company’s assets minus its liabilities.

Intangible assets (goodwill, brands, IP etc.) are excluded.

- This is not a one-way street – goodwill is a non-prductive intangible, but IP and brands can be very productive.

So the question is to what extent a large quantity of tangible assets is needed to generate revenues in a digital world.

- As well as the increasing significance of intangibles, it’s also the case that accounting rules have changed since the heyday of value (the 1970s and earlier).

What is needed is a valuation which strips out unproductive intangibles.

- This is sometimes known as fundamental value, and it was the subject of one of Joachim Klement’s recent articles (which looked at a new study from the University of North Carolina).

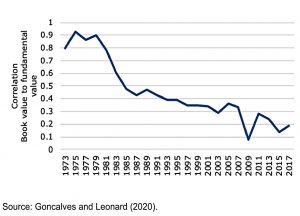

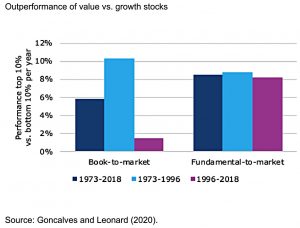

The fundamental-to-market ratio is very similar to the book-to-market ratio in the 1970s but starts to diverge more and more in the 1980s and afterward.

This is good, but I’d like to see a more nuanced version, which tries to distinguish between the productive and unproductive forms of intangibles.

More importantly:

When one then sorts stocks not on book-to-market ratio but instead on this fundamental-to-market ratio, the value premium does not disappear but remains constant over time.

Active vs Passive

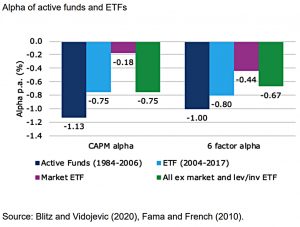

In a second article, Joachim looked at the performance of ETFs compared to active funds.

- He was reporting on a study from Blitz and Vidojevic of Robeco, who said:

From a pure performance perspective, the allure of ETFs finds little support in the data.

The study looked at US ETFs from 2004 to 2016 and found that “only” 40% beat the US stock market.

Joachim thinks that is a good result:

An ETF is supposed to track an index minus fees. I would expect 0% of ETF to beat their benchmarks after costs.

The paper compared the alpha of ETFs with active fund results from a Fama and French paper in 2010 (which admittedly covered active funds from 1984 to 2006).

- The ETFs had an alpha of 0-75% pa compared with -1.13% for active funds.

After correcting for the main six factors, ETF residual alpha was -0.8% pa, compared to -1.0% for active funds.

And as Joachim notes:

Since active fund fees have declined more rapidly than ETF fees, this gap may have narrowed even further in recent years.

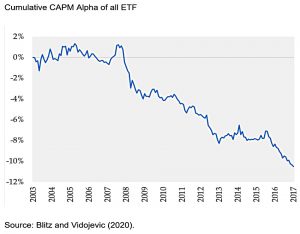

It turns out that sector and factor ETFs are dragging down the average ETF result.

Historically, ETFs were almost exclusively launched on broad stock market indices. It was only after the financial crisis that the number of sector and thematic ETFs increased.

As with active funds, narrower ETFs are launched when sectors are fashionable (ie. after periods of outperformance).

- Reversion to the mean leads to future underperformance against the broader market.

To that, you can add the dominance of the largest stocks in the main market cap indices over recent years.

As Joachim pits it:

ETF investors have consistent performance tracking an index, but it seems they are consistently wrong in choosing the index

Options insurance

Buttonwood reported on a spat between Nassim Taleb (of Black Swan fame) and Cliff Asness (who runs quant shop AQR) over whether using options as portfolio insurance is profitable.

- This is a tricky one for me since I admire both men a lot.

Taleb is an adviser to the Universa options fund which has stratospheric returns through the crash and has been pushing the idea that options are the best way to hedge.

- Work by researchers at AQR (such as Antti Ilmanen, who wrote Expected Returns) suggests that people overpay for insurance such as options, which means that in the long run, you would make money by selling (writing) options.

This fits the behavioural situation, too – you get paid to write options because the returns come when markets are doing well, and the losses arrive when markets are doing badly (ie. when no-one wants more losses).

- So my instincts are to side with Cliff.

Which is not to say that nobody should ever buy insurance, even though I am not a fan.

- The main thing is to get out of the habit of buying it routinely.

You should only but insurance when you will be unable to cope (financially or emotionally) with the loss you are insuring against.

- Otherwise, you are just handing money to the people selling you insurance.

Inflation

The Economist suggested that we shouldn’t worry about inflation – yet.

Never before have central banks created so much money in so little time. In the past three months America’s monetary base has grown by $1.7trn. America’s base-money-to-GDP ratio may grow by nine percentage points in the second quarter of 2020.

Since inflation is the consequence of too much money chasing too few things, it’s only natural that people should worry about it.

- As well as the extra money, the hit to production (and distribution) from lockdown means that we also have fewer things to buy.

And deflationary globalisation will undoubtedly take a hit from the pandemic.

But people said the same thing when QE was deployed in response to the 2008 crisis, and the inflation never arrived.

- One difference is that people are richer during this crash, thanks to government support.

But they are still saving more rather than spending – perhaps in anticipation of the storm ahead, or perhaps (like me) because there is nothing worth spending money on.

In the short-term, (despite last week’s spectacular numbers from the US) unemployment is generally likely to rise, and that is deflationary.

- As is the withdrawal of the furlough stimulus over the next few months.

A second article looked at the link between inflation and equity returns.

- The conclusion was that stocks offer a decent hedge over the long run, despite and inverse short-term relationship.

In principle, equities are a good hedge against inflation. Business revenues should track consumer prices; and shares are claims on that revenue. [But] rising inflation is associated with falling stock prices, and vice versa.

The mere fact that the average annual return over inflation for stocks since 1900 is 5.2% is a pretty convincing argument for their powers as a hedge.

- Compare that with the much-touted gold, which is basically flat.

Where is gets tricky is in periods like the 1970s, when inflation starts to rise.

[Because of the] “money illusion”, rising inflation leads to falling stock prices because investors discount future earnings by reference to higher nominal bond yields. The correct discount factor is a real yield (ie, excluding compensation for expected inflation).

Given the extraordinary valuations that investors will currently pay for future cash flows – particularly from firms which should do well in a low-inflation environment – the same effect appears to also work in reverse.

US public pensions

The Economist also reported on the worsening funding crisis in America’s public pensions.

- This situation is interesting because these pension funds are allowed to declare their own future returns on the funds they invest.

In contrast, private plans have to use corporate bond yields.

So the public plans declare unrealistic expectations (7% or 7.5%) which allow them to reduce contributions and sweep enormous deficits under the carpet.

- The crash will have made things worse, but the S&P has almost recovered now, so things look better than two months ago.

The average funding ratio of American state and local-government pension plans for the fiscal year ending in June 2020 will be 69.5%. Back in 2000 the average plan was fully funded.

Back in 2002 they paid an average of 7.8% of payrolls to fund pensions; in 2020 that contribution is likely to be 19.7%. If a more conservative accounting treatment were used, that rate would double.

The Centre for Retirement Research (CRR) estimates that by 2025, the worst eight funds will have just four years of benefits left in their pots, and the worst three will have only two years.

- Which means either higher taxes or lower benefits.

Quick Links

I have six for you this week:

- Aswath Damodaran said we should go back to basics when valuing stocks amid Covid-19

- And provided a DIY valuation for the S&P 500

- UK Value Investor stressed the importance of consistently covered dividends

- Alpha Architect wondered whether (low) interest rates can explain value’s underperformance

- And explained recent crappy returns from diversification and factor investing

- And Disciplined Systematic Global Macro Views explained that if you want convexity, you should hold the trend-following CTA.

Until next time